Lecture, exhortation, dissertation, harangue. These are all synonyms for “talking”, which is what the subject of actor/director/playwright Tim Blake Nelson’s new play Socrates — now playing at The Public Theater extended through June 2nd as the anchor of Onassis USA Festival 2019: Democracy is Coming — is best known for. In fact, he made a life, death and immortality out of being a relentless orator, so much so that a man born in 470 B.C.E. is still a topic of modern tongues and his tradition of thought, theories and philosophies are taught as required curriculum at any liberal arts school and part of many well-rounded university educations, even though he himself never wrote any of it down. His disciples, Plato in particular, carried the seeds of his wisdom (no doubt intermingled with some of their own ideas) on throughout history via their written text of his verbal musings. But while he did not intend or wish for his words to be written, in his lifetime, Socrates’ penchant for discourse and debates marked him a dangerous man, as is revealed in the play which takes place roughly between 430 B.C.E. when Socrates began “his mission” in Athens to 369 B.C.E. when Plato (still mourning the loss of his beloved mentor who died at the hands of hemlock poison thirty years before) takes on a new pupil. Thus the stage is set for Socrates.

The play begins with Plato meeting a defiant young man (the spirited Niall Cunningham), a new student he is asked to take under his wing. Their parrying of words is akin to fencing when the boy seeks, nay, demands that Plato (played by Teagle F. Bougere with elegance, intellect and panache) explain what happened to Socrates and why Athens turned against this great thinker. After some countering, Plato acquiesced and the tale unfolded through a series of flashbacks over what could have unraveled such a once adored Athenian and got him sentenced to death. For in Socrates’ case, his discourse was deemed dangerous and he had ruffled the wrong feathers one too many times.

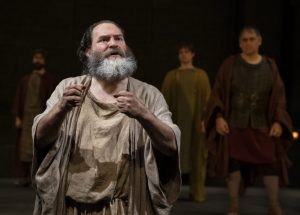

The titular character himself is portrayed with an alchemy of such depth and dimension, substance and subtlety, that even his most aggravating qualities are performed with absolute charisma that only a renowned actor — Michael Stuhlbarg — who could convey equal parts intellectual intensity with genuine likability could embody. Those are some gargantuan sandals to step into and Stuhlbarg proved he’s certainly up for the task. He takes on Socrates as one might approach one of Shakespeare’s most iconic leading men of a certain age. This is a juicy role he clearly relished sinking his teeth into.

Early into the performance, we encounter the boisterous “Boy’s Club” these mentally magnetic men found themselves in. All were delirious, drunk and were recounting tales of Socrates attempting to embarrass or unnerve the good-natured man. The goading “roast” was led by the charming and seductive Austin Smith, playing Alcibiades, who delighted the rowdy congregation of friends by grandiose professions of his adoration of the great man clearly beloved by present company, as he gave a visceral and vivid account of their rendezvous when the celebrated military man was a flawless youth “ripe for the plucking” who was showing off his flawless physique in the gymnasium. But — though Alcibiades would insinuate an intimate encounter had occurred just to make his mentor blush and entice uproarious laughter — he finally relented to tell the truth: as much as he had wished, Socrates was a perfect gentleman, and the only thing exchanged between them was a lot of penetrating discourse (not intercourse). This brash and blatant, even casual, “locker room talk” style of homoeroticism was both provocative and refreshing — because it was true.

Such love and affection between men (and like or agree with it or not, youths) was considered a higher, more profound connection and extended to the mental, emotional, spiritual and even physical realms as is seen and celebrated in Socrates. This is a male-centric production because those were the times, and as much as any and all of us can and should contest that in the 21st century, it was what it was and Nelson’s play is not afraid to be both true to the era, to call out its issues and also show how far we have (and have not) come.

But the bad behavior of Socrates’ “Boy’s Club” pals and wisdom-seeking groupies was the beginning of the end that led the thinker to trial and his eventual death. Acts of “Aristocratic defiance” and “blasphemy” from his companions smashing Hermes statues and profaning sacred rites put the philosopher under scrutiny. The rest of his downward spiral that propelled his undoing was of his own doing — by the sheer inability or lack of will and desire to keep his mouth shut. Many severe and unmerited injustices were committed against him and others but Athens was on edge at the time and was seeking and supporting those who’d keep quiet, stay in line and do as they were told. Socrates was never that kind of man so he was praised and then poisoned for his relentlessly questioning quality.

One of the most impressive elements of the contributions of the cast (particularly Michael Stuhlbarg who carried the loadstone of making such a significant historical figure so human and multifaceted), noble and notable director Doug Hughes and the playwright Nelson, is that Socrates is not portrayed as a victim, saint or martyr (as Joan of Arc was in the well-intentioned but misguided and faulty production at The Public in 2017) but as a mere mortal who is as brilliant as he is obnoxious, as kind-hearted as he is cruel and as stubborn and unyielding as he is inquisitive and curious. These forces have come together to paint the portrait of a man, a great one perhaps, though that is something the audience can decide for themselves, it is not thrust or forced upon them like the rigid dogma he was so against.

It is clear that Socrates was profound in his thinking and a stalwart defender of morals, ethics and truths who urged all around him to think more deeply and freely, to get to the root of all things and uncover the real meaning of concepts like virtue, justice, authority and wisdom. But for as many hearts and minds that he won over, he soured many more who held power and sway. They brought him to trial for bizarre charges such as “corrupting the youth” and “worshiping false gods” or “worshiping the wrong gods”. To that — how many hemlock concoctions would we need now if such accusations still held merit today? Certainly, the majority of the audience at The Public Theater would have been found guilty, which may be why it feels so relatable. However, there is a sense of preaching to the believers in this and many other democracy and politically-driven plays in the post-November 2016 America. It begs one to question and ponder (much like Socrates himself would have encouraged) — if he was around today, would Socrates be lauded as a groundbreaking, moral and justice-seeking shaker of the currently corrupt system, like a Bernie Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or more akin to the menacing presence of someone like Alex Jones from InfoWars, whose uncensored ramblings may be exercising freedom of speech under U.S. law, but are truly dangerous and corrupting nonetheless (not to mention irritating beyond measure)? Would such a powerful portrayal and rallying cry against obvious injustices ever be enough to sway the accusers who also believe they are in the right?

It was not the case for Socrates in life nor in this play, for any chance given to save himself, after an impassioned speech he would proceed to insert his foot deeper down his throat. But with Stuhlbarg’s particular magic and charm, teamed with Nelson’s witty writing that rarely took itself too seriously and Hughes deft direction, the production felt powerful and profound but not dour or too preachy.

But to backtrack to the points on the male-centric show and Socrates’ flawed human nature, there was a sole female in the production, Miriam A. Hyman — a dynamo actress who played Socrates’ wife Xanthippe. She first appeared onstage in what seemed to be a thankless token female role (though she threw in a good dose of sass and potency to make her intensity felt, even in that short introductory scene). As the production progressed, she further redeemed herself and empowered womankind from that ancient time as she ripped apart this mental giant, the great thinker and talker, revered or reviled by all of Athens and reduced him to what he was to her and their family — a bad husband and absentee father. She appeared, with little affection or fanfare, with two of their progeny at the hour before his impending death (one child feigned illness because the pain of the loss was too much). For his self-imposed moral obligation, Socrates was willing to abandon his wife and three children, who barely knew him, were hardly supported by him and clearly was unmoved by their presence. Even in his final moments, he denied her the intimacy of washing his back, saying “Plato will do it” — a dagger that Hyman as Xanthippe threw right back at him with bombast when she demanded that privilege as his spouse, then begged him once more to reconsider his fate for their family’s sake. This was perhaps the most meaningful twist and a major climax to the play (which ran about 20-30 minutes or so over what it could have to keep the pace, particularly in the end) because it completed the portrait of a man who is very complicated, flawed and deeply human. Stuhlbarg, Nelson and Hughes’ vision of Socrates paints him not as a martyr or superhuman mind, but someone we can relate to and learn from — in both his mistakes and his virtues.

SOCRATES began preview performances in The Public’s Martinson Hall on Tuesday, April 2 and the planned run through Sunday, May 19th has now been extended through June 2, 2019.

Public Theater Partner, Public Supporter, and Member tickets are available now. Full price tickets, starting at $75, can be accessed by calling (212) 967-7555, visiting www.publictheater.org or in person at the Taub Box Office at The Public Theater at 425 Lafayette Street.

The performance schedule is Tuesday through Friday at 7:30 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday at 1:30 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. The open captioning performance will be at 1:30 p.m. on Saturday, May 4. The audio described performance will be at 1:30 p.m. on Saturday, May 18.

The Library at The Public is open nightly for food and drink, beginning at 5:30 p.m., and Joe’s Pub at The Public continues to offer some of the best music in the city. For more information, visit www.publictheater.org

Friday, January 9, 2026

Friday, January 9, 2026